Rebel Without a Cause and “The Kids Today!”

By Arnold Anthony Schmidt

It seems as if people have always complained about “the kids today!” Those young people don’t respect their elders. They’re wild. Too sexual. The satirist Juvenal, writing in the second century, paints Roman youth – and, in fairness, pretty much everyone else! – as corrupt and degenerate. How can civilization ever survive? Almost a century later, the Roman playwright Plautus continues in this vein, with children running to romance and pleasure, and parents unable to control them, though those parents themselves often misbehave badly too! Authorities in Medieval Europe worried about how young people acted when they gathered unsupervised at night, and in the nineteenth century, some encouraged Sunday schools in hopes of controlling children uprooted by the agricultural and industrial revolutions. So, it’s not exactly true that Nicholas Ray’s 1955 Rebel Without a Cause invented the teenager or youth culture, as some claim.

At the same time, in 1950s America – and lots of other places besides – a culture flourished in which adolescents had their own music, dances, slang, and fashions. This came about for many reasons: post-World War II optimism as the economy boomed, a G.I. Bill that propelled people into the middle classes, and the movement of families to the suburbs. Anxieties loomed too, of course: about nuclear war, the sexual revolution, and racial prejudice. With the world shifting, parent-child relationships changed, and young people became ungrounded, seeking their own ways, discovering for themselves what it meant to be adult men and women.

Many of these issues appear in Rebel by Ray, his films admired by French New Wave directors like Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut, as well as by others like Martin Scorsese and Wim Wenders. Famous for exploring outsiders and conformity, Ray worked in many genres, like his 1954 Western Johnny Guitar and his 1951 Film Noir On Dangerous Ground. Ray gained renown for an Expressionistic style that used sets, cinematography, and performances to externalize his characters’ emotional states and communicate his films’ themes.

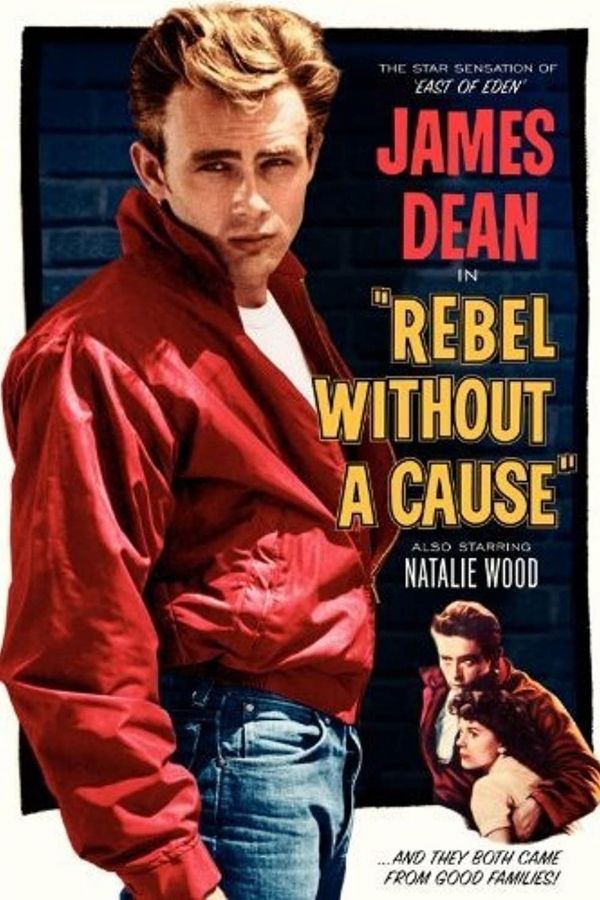

In Rebel, look for quirky camera angles and framing, scenes that emphasize color (like those with Dean’s red jacket), architecture (the Griffith Observatory sequences, inside and out), and the use of dissolves instead of cuts for scene transitions. In addition to working as a director, Ray also taught acting and directing at New York University, where Jim Jarmusch (later the director of Stranger Than Paradise, Down by Law, Only Lovers Left Alive) served as his teaching assistant.

Rebel recounts a day in the life of middle-class suburban teenagers, an early evocation of the generation gap, with many elements now common to the “coming of age” genre in that era. There’s family conflict, a knife fight, a “chicken” race, and love scene. The film, which takes its title and little else from a contemporary sociology book, reminds audiences of Marlon Brando’s famous line in the 1953 The Wild One. When someone asks the leather jacket-wearing, motorcycle-riding Brando “what are you rebelling against?” he responds “Whadda you got?” Like Brando, Rebel‘s star James Dean burst on the scene as a symbol of his generation, with both of them brandishing a swaggering masculinity and eroticism that challenged contemporary norms.

Dean and Brando shared more than attitude, though. They’d both studied Method Acting, an approach that differs from more traditional training by using the individual performer’s personal psychological and life experiences to create a character, rather than relying on external movements, facial poses, or body gestures to convey emotion. (I’m greatly simplifying, of course, and most actors have experience in both schools, whose instructors in no way exclude all ideas from other approaches.) Since its beginnings in the early twentieth century, the Method created generations of performers, from Sally Field and Marilyn Monroe to Montgomery Cliff and Paul Newman, among many others as well.

This approach gives actors license to improvise, and directors of Dean like Ray in Rebel, Elia Kazan in East of Eden (1955), and George Stevens in Giant (1956) all took advantage of spontaneous moments in his performance. Notice the scene in Rebel when Dean confronts his father, played by Jim Backus. The camera looks up almost distortedly from Dean’s point of view into the faces of the adults in the police station. Then Dean explodes with the words “you’re tearing me apart!” Similarly powerful moments occur in Eden, in Dean’s reaction to the failure of his frozen food scheme and discovery of his mother, and in Giant, where he reportedly played the drunk scene so drunk that parts of his slurred voice had to be dubbed afterward.

Alongside Dean, Natalie Wood stars, in a film that brought her to prominence as an adult actor. Her many roles include the little girl in Miracle on 34th Street and Maria in West Side Story (though the uncredited Marni Nixon did her singing). During Wood’s career, she received three Oscar nominations: Best Supporting Actress in 1955 for Rebel Without a Cause, and Best Actress in 1961 for Splendor in the Grass and in 1963 for Love with the Proper Stranger. She died tragically in a boating accident whose cause remains uncertain.

Backus portrays Dean’s father, whose conflicts with his son revolve around the question of what it means to be a man in contemporary society. Audiences know Backus from Gilligan’s Island and as the voice of Mr. Magoo, as well as Films Noir like A Dangerous Profession (1949) and Deadline – U.S.A. (1951), and comedies like It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963) and The Beverly Hillbillies TV show.

Sal Mineo appears as a friend of Dean and Wood, and his psychological fragility precipitates tragedy. His moving performance led to a best Supporting Actor Oscar nomination.

Starting in 1954, Dean began racing cars, and he drove competitively a few times in Bakersfield and Palm Springs, not winning, but finishing in the top of the field. His love for cars took a deadly turn, however, when the following year his Porsche crashed into a car that unexpectedly pulled in front of him. The cause of the accident remains unclear. The courts cleared the car’s driver of wrongdoing and blamed Dean’s speed, but an officer on the scene claimed the evidence showed Dean had followed the speed limit. In any event, Dean’s death led to him receiving two posthumous Oscar nominations. His performance in East of Eden, the only film released before his death, earned him a nod for the 1956 Best Actor Academy Award and his work on Giant led to his second posthumous nomination in 1957.

In the company of Brando, Elvis Presley, Little Richard, and many others, James Dean captured a moment of 1950s social transition, as young people began to emerge as a social, economic, and political force in the sixties and beyond. Ray filmed Rebel Without a Cause in Warner Color in the wide Cinemascope format (2.35:1 aspect ratio), so if you’ve never seen it on the big screen, you won’t want to miss it!

Arnold Anthony Schmidt is a Turlock-based writer who teaches British Literature, Creative Writing, and Film at California State University Stanislaus.

Most recently, the Dramatists Guild West hosted a reading of Schmidt’s comedy for young audiences, Pirates, Mermaids, and the Girl Who Couldn’t Swim. That play, and a monologue about 1931’s anti-Mexican “La Placita” riots, appeared in Grass Valley’s 2021 NorCal/Nugget Fringe Festival.

Schmidt’s The Super Cilantro Girl, based on stories by U.S. Poet Laureate Juan Herrera, premiered at Turlock’s Lightbox Theatre. In 2019, California State University, Fresno brought the play to area schools, where it was seen by more than 6,000 children.

Schmidt’s film credits include serving as Assistant Producer on “The Silence,” an American Film Institute production nominated for a 1983 Academy Award best short dramatic film; writing a screenplay for Deja Vu, a 1984 Cannon Films feature starring Jaclyn Smith, Nigel Terry, Shelley Winters, and Claire Bloom; and writing the story for the “Tommy’s Lost Weekend” episode of the Warner Bros. sitcom Alice, nominated for a 1985 Emmy Award and awarded a 1986 Letter of Commendation from Los Angeles County for its treatment of teenage alcoholism.