Kiss Me Deadly: A Classic Film Noir with a Twist

By Arnold Anthony Schmid

Admit it: when you think about film noir, you don’t associate it with the nineteenth-century Pre-Raphaelite poet Christina Rossetti! Yet the suggestive role played by Rossetti’s 1862 sonnet “Remember” in Kiss Me Deadly illustrates only one of the many things that make this film stand out.

Based on the 1952 Mickey Spillane novel, the action swirls around possession of a mysterious suitcase, whose contents we learn at the end. Or do we? The movie concludes with one of film history’s most famous and enigmatic climaxes! Early on, the movie’s first victim, quoting the poem, urges detective Mike Hammer to “Remember me” before she dies. A lot of action happens as we hurtle toward the end. We encounter murder and mayhem, kidnapping and pursuit as the film’s characters and the audience attempt to understand what makes the suitcase’s contents so valuable. And idiosyncratically, the words of Rossetti’s poem echo here and there.

Critics situate films noir, most produced in the 1940s and 50s, in the context of the Second World War which, with most men away in the service, brought women into the workforce. This gave many women as sense of independence and empowerment, which they reluctantly relinquished when the war ended. Through a sort of demonic inversion, this anxiety about strong women appears in the notion of the femme fatale, a figure with her own ideas and agency: powerful, tempting, and dangerous. In film noir, a “virtuous” woman often contrasts with the femme fatale, contrasting a “good” girl with the “bad.”

Beyond social history, film noir also has literary antecedents. In plots adapted from the pulp fiction magazines of the thirties and forties, many films noir drew hardboiled detectives like Dashiell Hammett’s Sam Spade and Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe. In addition, scholars link film noir’s ethical relativism to the Existential philosophy of the World War II period. Writers like Albert Camus and Jean Paul Sartre followed Nietzsche in seeing people as free to act as they saw fit, though always following an internal ethical code. We see this in films noir like John Huston’s 1941 Maltese Falcon, where Spade inhabits a world marred by marital infidelity, police brutality, and rampant criminality. Through it all, Spade attempts to remain true to his moral code, which requires evil doers to receive punishment. In the end, he turns even his lover Bridget O’Shaughnessy over to the police. Here, as in Kiss Me Deadly, characters live in a world with no ethics except those they create for themselves. Like the classic existential hero, they must both make those rules and adhere to them.

Viewers best recognize film noir by its art direction’s canted angles (not perfectly horizonal or vertical), black-and-white cinematography, deep focus, and jazzy soundtracks. These films generally tell dark urban tales. Trying to figure it all out, the private eye reasons and fights his way through the city’s dirty underbelly, facing hoodlums, corrupt cops, and femmes fatales. If the plots for these films come from the pages of pulp fiction, the look comes from Expressionism. A generation of expatriate filmmakers from Germany’s famous UFA studio fleeing the Nazis introduced to Hollywood the artistic movement that attempted to externalize emotional responses and psychological states.

One way they achieved that was through signature cinematography featuring a chiaroscuro lighting style, modeled on paintings by artists like Caravaggio, Artemisia Gentileschi, and Rembrandt. Noir’s Low Key Lighting features a bright primary light that casts strong shadows as it illuminates the scene, with less brilliant fill lights modeling the set. (Using only a single bright key light without any fill would make the scene appear flat; fill lights provide a sense of depth and emphasize three dimensionality.) In comedies, romances, and musicals, filmmakers use High Key Lighting with less contrast between the key and fill lights to create evenly lighted, well-illuminated sets with few shadows. Horror and crime movies like Kiss Me Deadly use Low Key Lighting to suggest psychological interiority, with a chiaroscuro style that carries us literally and figuratively into the darkness. Look for shadows, reflections in mirrors, and exterior lights flickering through venetian blinds.

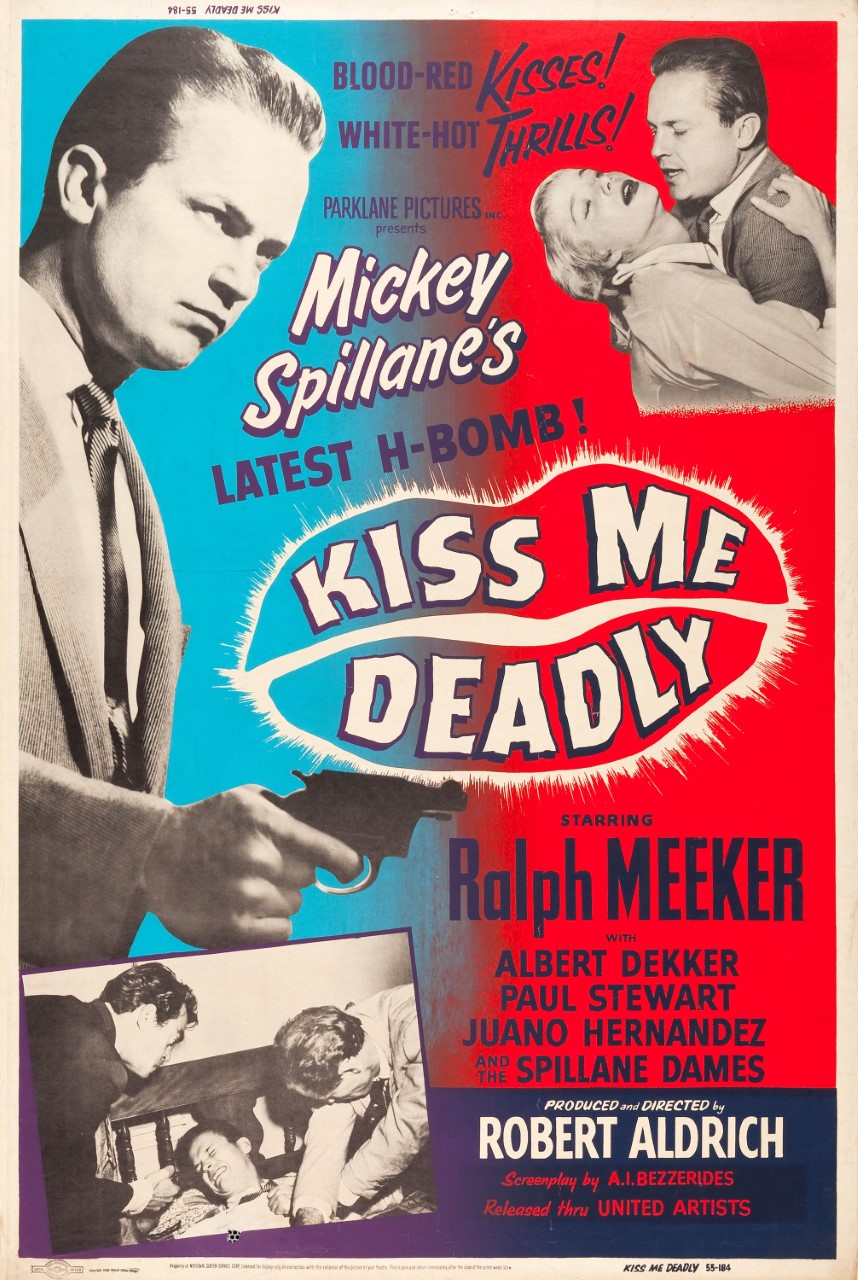

Kiss Me Deadly was directed by Robert Aldrich, who helmed a wide range of films, from westerns like Apache (1954) and Vera Cruz (1954), to war films like The Dirty Dozen (1967), to psychological thrillers like What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962) and Hush…Hush, Sweet Charlotte (1964). As an aside, he also directed The Frisco Kid (1979), a comic tale about a rabbi’s adventures in the wild, wild west, recently featured in a State Theatre Zoom discussion during the COVID lockdown.

Ralph Meeker, who portrays detective Mike Hammer, appeared on Broadway in Mister Roberts and Picnic, and in dozens of films, including Stanley Kubrick’s Paths of Glory (1957). Viewers may remember Meeker best from his long television career, beginning with prestige dramas like Playhouse 90, westerns like Wagon Train, Sci-Fi shows like The Outer Limits, and comedies like Room 222.

So, what makes Kiss Me Deadly such a stand-out film? First, it’s not a traditional noir, despite having many trademark noir elements: a shamus, an urban setting, night scenes, and lots of criminal goings-on. It differs from classic films noir in important ways. For one, it resembles Cold War noirs like Samuel Fuller’s Pickup on South Street (1953); in both, a political element intrudes to provide a bit of ethical grounding. If we’re unsure what the suitcase contains, we remain certain that things will be far worse if the bad guys manage to grab it. Next and most obviously, Kiss Me Deadly has no femme fatale; here, men rather than women figure as instigators of evil. And finally, there’s Rossetti’s poem, make of it what you will.

Kiss Me Deadly has influenced such fervent admirers as directors Jean Luc Goddard, Francois Truffaut, and Quentin Tarantino. Odds are you’ll find yourself as fan as well.