“Three Powerful Biopics: Oppenheimer, Napoleon, & Maestro”

By Arnold Anthony Schmidt

When it comes to storytelling, people who enjoy movies put filmmakers in a peculiar situation. On the one hand, we want something familiar: a story of romance, crime, mystery, sci-fi, whatever we’re in the mood for. At the same time, though, we want something different. A new take on an old theme. A fresh treatment, an unusual perspective on a recognizable genre. It’s not surprising, therefore, that so many films, books, songs, and even video games resemble those that came before, but differ from them just a wee bit.

Critics condemn the “same, but different” if it feels too formulaic, which puts filmmakers in a bit of a bind. When it comes to “true life stories,” cinema biographies generally follow the familiar narrative arc of “rise, fall, and redemption.” The main characters usually start out unknown, unsuccessful, and broke. They struggle and accumulate vast success in their fields, then encounter some setbacks (drugs, infidelity, health issues, all the above) which to some degree or other they overcome – if only temporarily or symbolically – by the movie’s end. That’s the general structure, as exemplified by Michael Apted’s Coal Miner’s Daughter and similar films.

Sometimes, filmmakers make the biopic’s familiar “rise, fall, redemption” structure different by “bookending” the story. They open the movie with a key scene from the triumphant conclusion, then flash back to tell the story from the beginning. Then follows the expected sequence of struggles, successes, setbacks, and ultimately closure. For example, Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi opens when the protagonist’s fame and influence have reached their pinnacle, just before his murder. The film then flashes back to his early struggles for social justice in South Africa and tells the story of his life up to that final gunshot. This death scene, seen twice, “bookends” the story at the beginning and end.

Or think about Bryan Singer’s Bohemian Rhapsody, which follows Freddie Mercury’s rise and fall, opening and closing like Ghandhi with bookended scenes, these revolving around a famous concert. In between, we see Mercury’s growing success, coupled with his self-destructive behavior. Even Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis, though taking a different tack by focusing on the role of his manager, follows a similar trajectory. Opening with his manager’s health crisis, it follows Elvis, young and unknown, as he becomes successful, has his own emotional, artistic and health crises, to climax with him, though near death, still a powerful singer and entertainer. The ending bookend of his manager ties things up, if only somewhat.

Such bookending affords viewers one of cinema’s great aesthetic pleasures: of forming an opinion about a character or situation, only to change it. When viewers see the incident the first time in the beginning, they form certain convictions. Then they watch the film and ultimately see that same incident at the end. When they do, what viewers have learned along the way provides context that challenges those first impressions. At the beginning of Gandhi, we see him shot and have no context for what’s going on. By the end of the movie, we see the shooting again, but have a great deal of context and understanding. Bohemian Rhapsody and Elvis affect audiences in the same way.

Critics often consider this “rise, fall, redemption” arc facile, and lament its familiarity, even when directors use bookended scenes, flashbacks, and other devices to make it seem fresh and new. Still, it’s become a mainstay of cinema biographies for the simple reason that it works. Three 2023 biopics, not all equally accomplished, embrace this formula, making it their own by occasionally diverging from it.

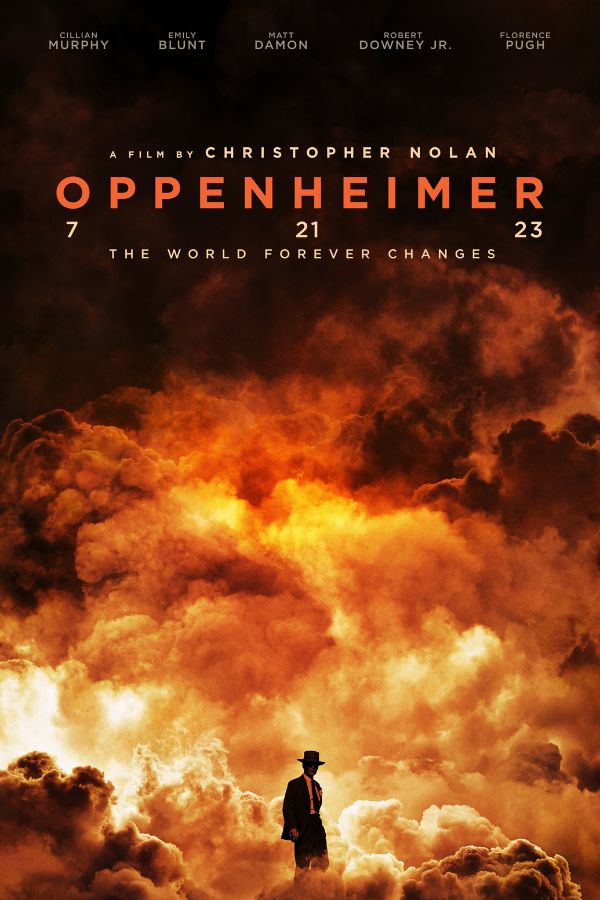

Consider the first and most artistically successful of these, Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer. The story moves from Robert Oppenheimer’s unstable student days, weaving its way through a series of narrative threads: his scientific development, political activism, war efforts, and Cold War reaction, as well as relationships with his wife and mistress. The troubled student-scientist gains notoriety quite quickly, ultimately heading the Manhattan Project which created the atomic bomb.

After Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Oppenheimer rejects his role as nuclear posterchild. Instead of supporting development of America’s arsenal, he urges the sharing of scientific knowledge and arms control, positions that lead to conflict with the powers that be. These positions, coupled with his youthful political activism, result in the revocation of his security clearances. Ultimately, an award by President Johnson rehabilitates his reputation, though a final flashback with Einstein reinforces the film’s central message about the danger nuclear weapons pose to humanity’s survival.

Although Oppenheimer follows the familiar formula — rise, fall, redemption – the movie benefits from myriad conflicts and rich explorations of character psychology. Here, the formula provides a simple structure which scaffolds the film’s complex historical and biographical narrative. And advances its Faustian themes as idealism and knowledge lead to cynicism and destruction.

Ridley Scott’s uneven Napoleon deviates a bit from the “rise, fall, redemption” formula. Here, the title character begins as an artillery officer, rising to become emperor of France while confronting crises in the boudoir and the battlefield. The film ends leaving Napoleon largely unredeemed, talking with children and writing his soon-to-be-famous memoirs. He dies hugely influential, but defeated; world famous, but isolated and alone.

If Napoleon remains a worthy, but not entirely satisfying movie, don’t blame its varying from the “rise, fall, redemption” formula. Rather, the fault lies in its bifurcated story. This epic narrative contains the makings of two fine films, the first a widescreen portrayal of Napoleon the political and military hero, the second an intimate Indy-style affair about Napoleon the man, his sexual/emotional demons, and his wife Josephine. The existing film combines these two story ideas, following the Corsican’s military and political rise and fall, coupled with — but not mirrored in — the success and failure of his relationships.

Incongruities arise because the two stories don’t clearly reinforce each other. They don’t “rhyme.” The events of the private sphere fail to find specific echoes in the public. We’re told about Josephine’s importance to Napoleon, but don’t see it. He claims that he owes her his success, but the audience never learns why. The plot needs to suture the private and public stories more closely together. We need the film to show us how the private influences the public person and visa versa. Napoleon uses shorthand to suggest this, but falls short.

The third of these biopics, Bradley Cooper’s Maestro, also avoids the “rise, fall, redemption” line, here bookended by scenes of an interviewer questioning Leonard Bernstein. Early in the film, we encounter the young composer and musician who immediately becomes famous after standing in when a prominent conductor becomes ill. This leads to his successful rise, though we see little of his fall beyond images of a failed marriage and bad behavior. His unhappy childhood garners a brief mention, but the film communicates little of his motivations or psychological makeup.

The movie tries, like Napoleon, to link Bernstein’s professional rise and fall with his personal life, but also shows little connection. The composer’s marriage seems almost beside the fact to him, something done blithely along the way and much more about him than about them. His wife enters their marriage open mindedly, and presumably at first takes from it what she wants and expects. Later of course, comes unhappiness, as revealed in an almost overwhelmingly strong argument scene. But instead of showing the relationship lessons Bernstein may have learned, lessons perhaps most poignantly presented in Noah Baumbach’s Marriage Story, we see Bernstein in a disco philandering with the student. The interviewer’s opening and closing scenes bookend the narrative without providing any real perspective or resolution.

When analyzing narrative, critics often ask how characters change from beginning to end, what they learn. If characters don’t change, critics ask how the audience’s attitude toward them changes? Significantly, Maestro shows Bernstein learning nothing. He has experienced unhappiness, but seems little changed. Though realizing that his actions cause pain, he fails to take personal responsibility. Maestro doesn’t even present enough of his artistic creation to explain away his behavior as the stereotypical tortured artist – the film all but omits Bernstein’s most famous achievements, beyond brief references. Maestro’s originality comes from avoiding the “rise, fall, redemption” motif, and a less myopic focus on Bernstein’s private life might have made that structure work better.

Now don’t get me wrong. I enjoyed these movies. You’ll want to see all three, each quite strong and boasting incisive direction, powerful performances, and superb production values. I draw your attention away from all that, however, to the structure beneath. Like the skeleton of a skyscraper that holds the building aloft, the organization of narrative events holds the film’s story together. As you analyze these films, think about the form that these men’s stories take. How does their structure affect you? How do you respond to the “same, but different” and “rise, fall, redemption” formulas?

Extra credit for analyzing the structure of the delightful Barbie (not precisely a biopic, but you get the idea) using the same criteria!